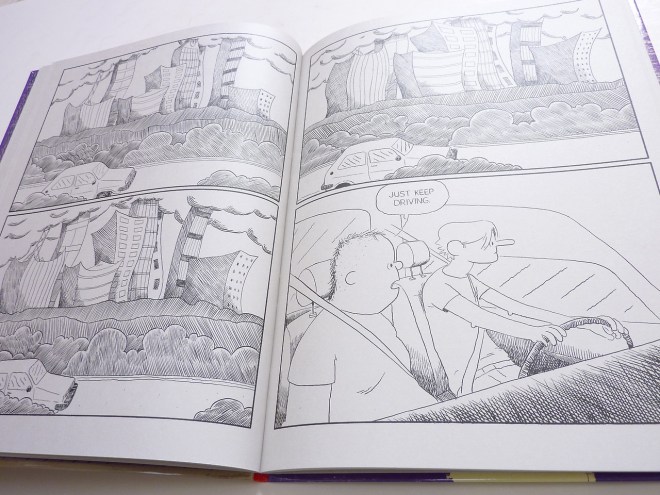

East of West seems almost custom-designed to foil synopsis, but here’s me trying: it takes place in 2049 in an alternate America that was wracked by extensive civil wars, and has split into seven nations, including the Confederate States, a unified Endless Indian Nation, and New Shanghai. Somehow these seven nations, or at least a number of their highest-placed members, share a holy text — a pieced-together book of enigmatic apocrypha called The Message, which details (and immanentizes) Armageddon.

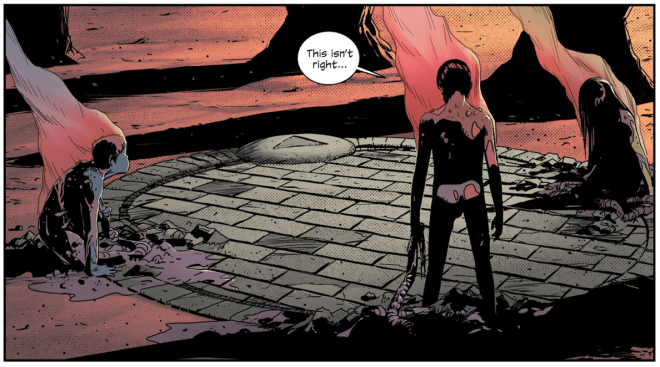

Jonathan Hickman’s richly layered story begins when, as foretold in The Message, the Horsemen of the Apocalypse awaken, embodied as children and eager to bring about the endgame, but surprised to discover that they are only three. Death, it seems, has broken off on his own.

He’s riding a pale robot-horse across the seven nations, murdering acolytes of The Message in key positions. At first, his purposes are oblique, but soon become clear: Death is actually a little bit of a sap, and he’s trying to track down the woman he loves, who once loved him back.

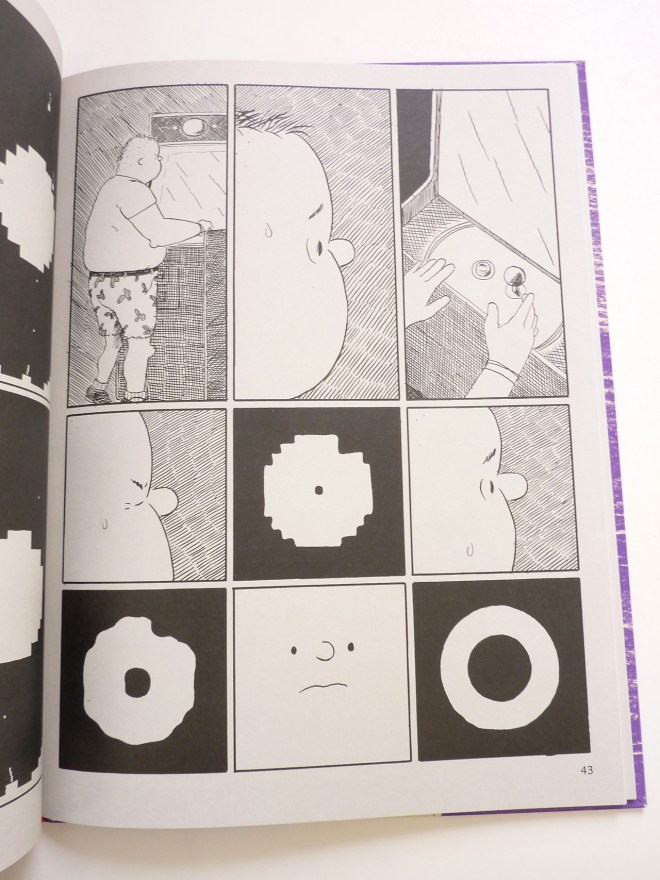

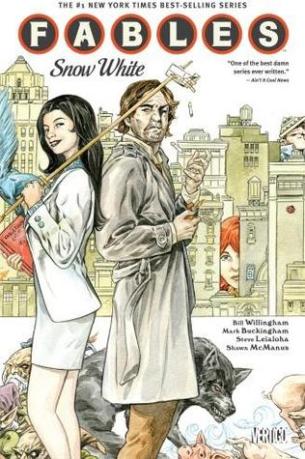

Like Emma Rios and Matteo Scalero, Nick Dragotta is a highly skilled and promising professional who’s done a fair amount of work for the big two and then taken a quantum leap into auteur cartooning with an astonishing new Image series. Books this vital bring new meaning to the phrase ‘creator-owned’ — not just the intellectual property but the voice itself, so fully developed and alive on the page, the world-building so immersive, so effortless and thorough, that it’s impossible to imagine anyone else drawing it. This is a cartoonist’s voice in perfect tune with the subject matter, the space where the stark lyricism of John Ford meets the hard, cold sheen of Ridley Scott. Dragotta can take something as silly as a cowboy riding that aforementioned robot-horse with a laser cannon for a face and render it so artfully, so matter-of-factly, that you don’t blink.

East of West is a baffling book, and it demands rereading. It wants to be puzzled over and dissected like an esoteric text. Why, for instance, does a book set in a shattered and rejiggered United States never offer us a map of the new territory?* Because it wants to disorient us, is my guess. It doesn’t just want to tell a story about the wild west — it wants to BE the wild west, a mapless, trackless wilderness in which we have to find our own way. It’s the worst of both worlds, the lawless west and the sci-fi distopia — the desolate unsafety of the uncharted territory meets the tight social net in which we’re all pawns of forces beyond our control. The tension between security and freedom has been resolved by eliminating both.

So what we have on our hands at first appears to be some kind of retro-futurist hard-science gnostic political-intrigue western. But Death’s longing to be returned to his wife and child are the hook on which the wild digressions and house-of-cards world-building of the series are hung. Death is what passes in this book for a protagonist (if a story this huge in scope and this resistant to reader-identification can even be said to have one), and he has a formality, a slow, lanky, Gary Cooper courtliness at odds with the river of carnage he leaves in his wake.

There is something appealing about him. The characters in East of West are motivated occasionally by lust, or greed, but mostly they are motivated by pure grievance and hatred. The only true cooperation in the book is an uneasy collaboration among sworn enemies in the interest of burning the world to the ground. It is never explained, at least thus far, why they want to bring about the end times — but in a world this dead-eyed, this calculating and vicious, it doesn’t seem totally counter-intuitive. Death, though just as violent and selfish as the rest of the characters in East of West, is motivated by devotion and ardor. So it turns out that East of West is a soul-sick romance, with a sense of strangled longing that pierces like an arrow through its huge, dark expanse. For all of its futuristic trappings and alternate past, it is about our modern world: irredeemable, possessed by hatred and avarice and resentment, seemingly on the verge of toppling into ruin, yet still, against all odds, animated by the capacity for love.

*As Rick and Justin pointed out in the comments, there IS in fact a map included in an early issue of East of West. I must have missed it the first time through, though, and didn’t see it in my recent re-read of the trade. I fully embrace the confusion that’s ensued!

– Josh O’Neill